Scott Morrison’s push for Australians to download the Covid-19 App appears to be meeting with mixed success. There are a couple of reasons for this.

Firstly, so far 4 million people have downloaded the App.

The government claims that, with this level of compliance, it’s approaching the threshold 40% for the App to be effective.

It is difficult to assess whether this is correct.

There are 18 million mobile phones in Australia. There will also be multiple phone per person. So, it’s difficult to assess what level of take-up is necessary. Four million is only just over 20% of 18 million. So, it really depends how you count: total number of phones or total number of people with phones.

If someone has more than one phone, they really need to download it onto all of their phones.

Secondly, there is not universal support for downloading the application.

A range of concerns have led to some high profile people not downloading the App.

One is Independent Federal MP Andrew Wilkie.

Wilkie, who has worked for the Office of National Assessments (ONA) and was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Australian Army, has stated

“it is not my intention to use the Federal government’s pandemic phone app until I’m convinced it’s effective and secure. Until then I remain unconvinced that the likely low uptake rate in the community will achieve anything other than give people a false sense of safety and encourage them to drop the personal health precautions

In addition, I don’t trust to government implement, manage and safeguard the system without risk of leaks or hacks or to limit the use of the system to the pandemic.”

John Roskam, who heads the Institute of Public Affairs think tank, which is influential with many Liberal MPs, said the app was “very bad and very dangerous”.

“There is no way the government or any technology company can be trusted with that information, and guarantees the government gives are worthless,” he said. “It is authoritarian and goes against everything the Liberal Party stands for, and it is incredible it is even being considered.”

Independent MP Zali Steggall tweeted that a “lack of trust in, and transparency by, government is a major hurdle to people accepting [the] contract tracing app”.

Barnaby Joyce has also refused however this may not have been an influential decision.

Morrison has also unwittingly established a systemic problem for himself. The concern about security, the trustworthiness of governments, the lack of transparency over the source code and the effectiveness of the application itself may have the impact of stalling the number of applications downloaded.

The dilemma is highlighted in a paper by behavioural economist Christian Thöni of the University of Lausanne: The majority — about 60 per cent — are “conditional cooperators”. They cooperate if they believe others will cooperate.

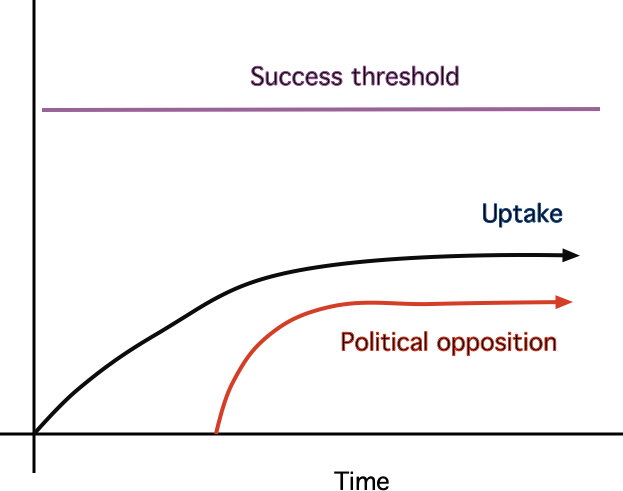

A rapid uptake of the App would have created what is known as a “Success to the Successful” structure, where the number of people downloading encourages others, the conditional cooperators, to do so.

Unfortunately, if this does not happen then the result will be a “Failure to the Failing” structure. With the low numbers of people downloading encouraging others not to download.

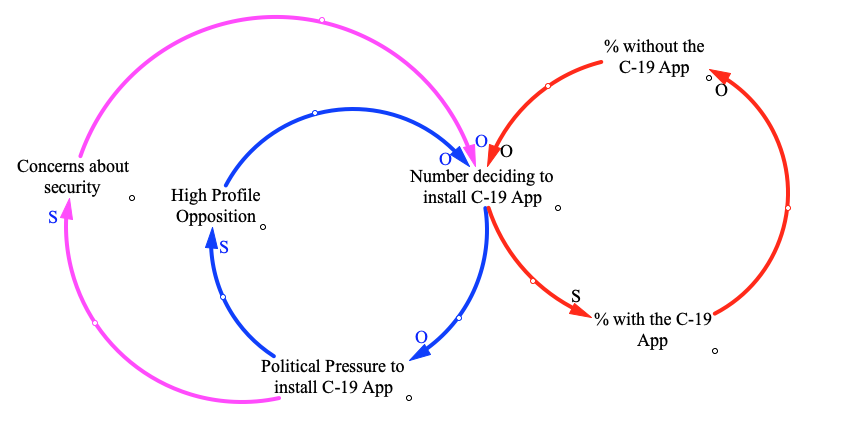

This Causal Loop Diagram shows how this dynamic is established.*

The problem for Morrison is that, unless the initial download momentum is strong enough to convince the conditional cooperators, he will not get the numbers necessary for the application to be successful.

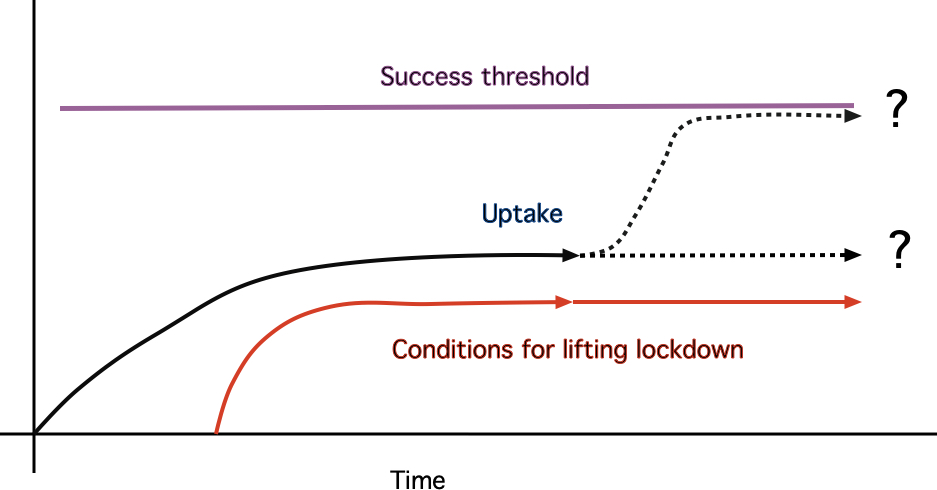

Making the success of the Covid-19 App a condition for easing the conditions of the lockdown may be sufficient to reverse the negative effects of the left-hand side of the CLD.

But if it isn’t, then Morrison will effectively be punishing the people who have complied with the government’s wishes and that could cost him significant political capital.

* An “S” end of the arrow means that the variables move in the same direction: if the first goes up the second goes up, if the first goes down, the second goes down. An “O” means the variables move in the opposite direction.