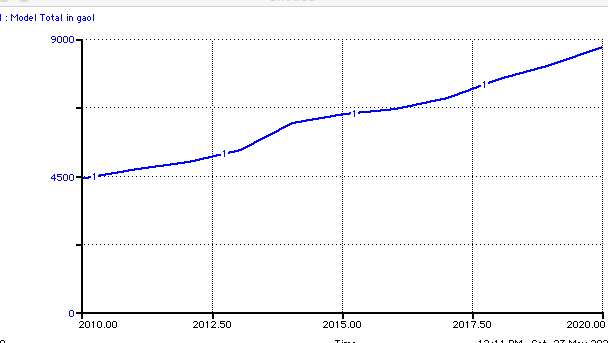

The first stage of the model showed a population of 5 million receiving a two-dose vaccine over two years with priority going to administering the first dose.

The model showed that after two years, 4.65 million people were vaccinated and 340,000 remained unvaccinated. The vaccination uptake was 20% of the unvaccinated population receiving their first jab each month and becoming available for the second within two months.

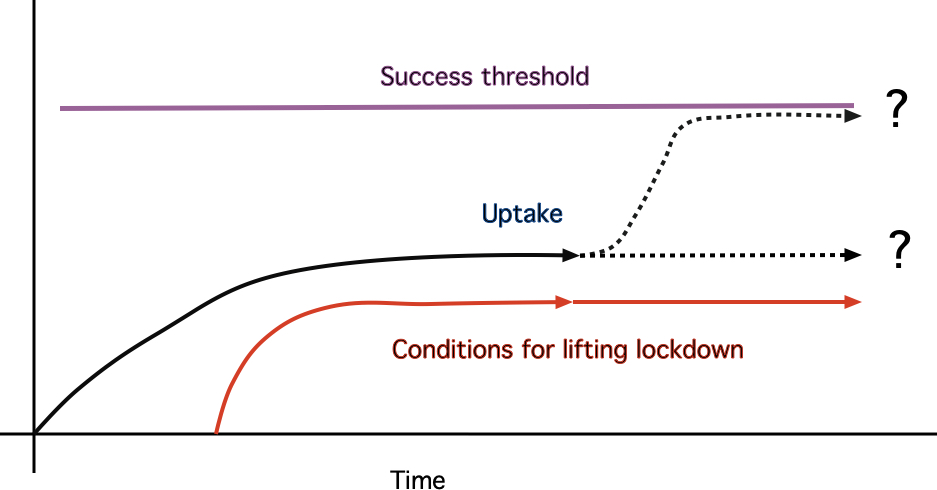

The second iteration of the model shows an outbreak of Covid-19 in the first month of the rollout. It sent shockwaves through the population and the vaccination rate roses from 20% to 50%.

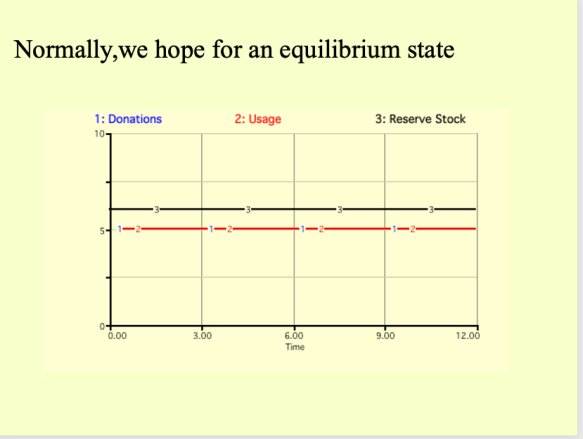

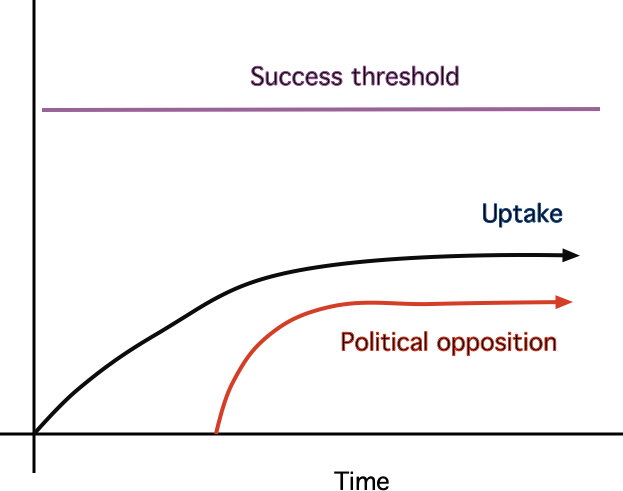

The graph on the right shows the progress without shock. It takes two years before the population reaches 4.6m vaccinated people. That is 92% and most people would be happy that with that outcome, even if it did take two years.

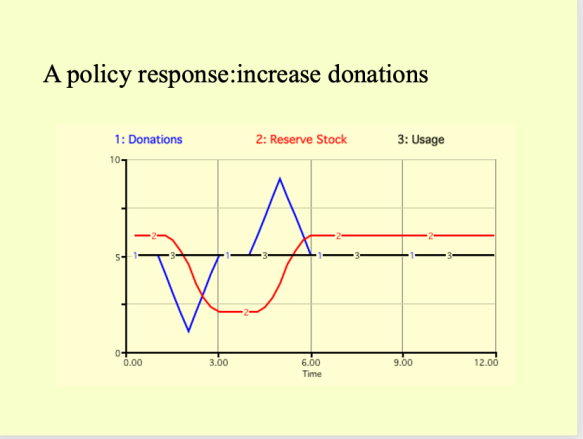

The right-hand graph shows the impact of a Covid outbreak, which shakes the population out of its complacency. First, notice the early jump in the population with one jab (blue line). This results in a rapid fall in the unvaccinated population and a rapid rise in the population with two jabs.

The residual vaccinated population in the left-hand graph is almost certainly more realistic. However, experience in Australia shows that vaccination rates are increasing as a result of Covid infections and lockdowns.

Then everything goes pear-shaped.

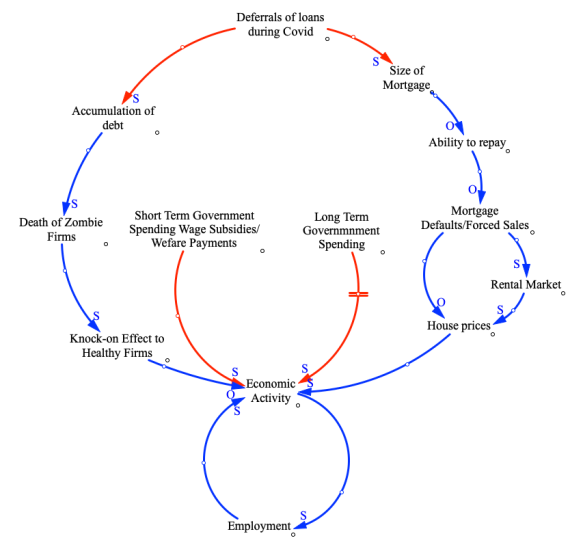

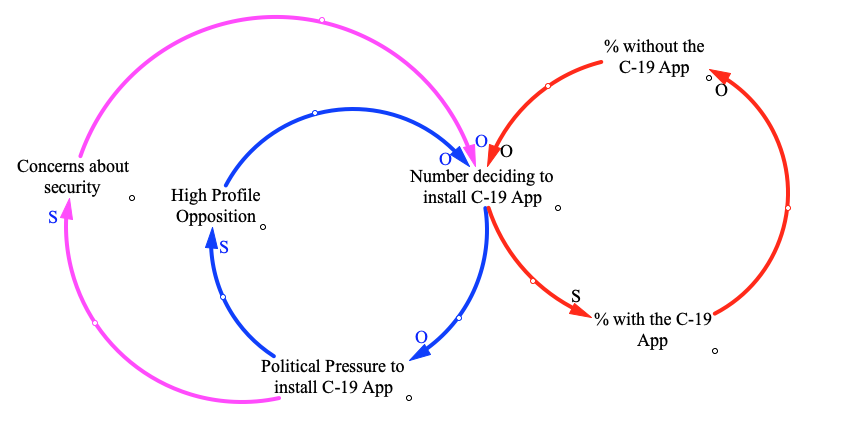

Early clinical information about the government’s preferred vaccine indicates risks of blood clotting in certain age groups. The chances are low, but several countries, which have secure supplies of other vaccines, call a halt to the administration of the only vaccine the Australian government has access to.

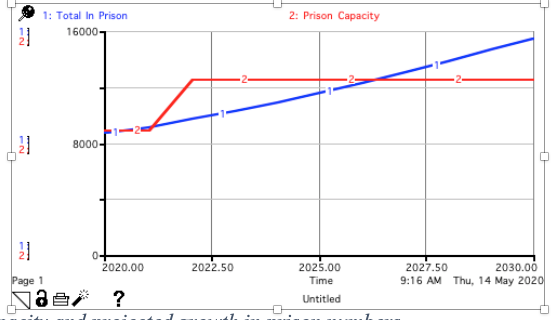

Health Authorities recommend that the vaccine should not be used for people under 60 until new advice is received on the risks of blood clotting. The take-up rate of the vaccine drops from 30% to 5%. Worldwide demand means no new vaccine supply will be available within 12 months.

Projections indicate that the rollout will be stalled for the next 24 months, with only those prepared to accept the low risk of blood clotting being vaccinated.

After 24 months, modelling suggests that roughly half the population will be fully vaccinated if the health authorities do not clear the current vaccine.

After 12 months, the government is able to secure supplies of a new vaccine, which does not have the associated clotting risks. Once that becomes available, vaccine hesitancy appears to have been overcome.

The impact of the population with one jab can now be seen. As first movers, they were influential in getting people vaccinated, but the news of the problems with blood clotting slowed vaccination rates. When a new vaccine arrived shortly after 16 months, vaccination rates jumped again.

Under all scenarios in this model, the population is vaccinated within two years.

There are some assumptions in this model that may not be true in the real world. These can be simulated in the model.

It is possible to model scenarios where there are supply shortages and logistics problems.

The big elephant in the room is what will happen while it takes two years to reach 80% vaccination.